Working Papers Series #2

Why do the gods look like that?

Material Embodiments of Shifting Meanings

John McCreery

Independent Scholar, The Word Works Ltd.

© 2010 John McCreery

Open Anthropology Cooperative Press

www.openanthcoop.net/press

Forum discussion in the OAC network.

Download as PDF, EPUB, MOBI.

Prologue

I invite you to imagine a tourist visiting Japan. She has seen a number of Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines. Friends take her to Yokohama’s Chinatown for dinner. On the way to the restaurant they stop for a look at a Chinese temple, the Guandi Miao. The vivid colors and baroque decoration of the Chinese temple contrasts sharply with the subdued simplicity of Japanese Buddhist temples and shrines (Figures 1, and 2). The red face and piercing eyes of the Chinese deity on this altar (Figure 3 differ dramatically from the lowered eye-lids and meditative serenity of the Japanese Buddhas (Figure 4) she has seen. In Japanese Shinto shrines, the gods are not visible at all (Figure 5). The question she asks is simple but profound: “Why do Chinese gods look like that?”

When, however, we turn to the anthropological literature on Chinese religion, we discover, as Wei-Ping Lin points out, that anthropologists have paid little attention to the material forms that gods take in their statues on Chinese altars (2008:454-455). Instead of looking closely at god statues to discover what they might tell us about the gods in question, we have tended to look through god statues in search of something else. The statues themselves are treated as arbitrary signs, as, in effect, texts, whose material form is of no intrinsic interest.

If we adopt, instead, an art historical or connoisseur’s perspective, we encounter a different approach. Here the primary focus of interest is iconographic details that that identify the god or the style in which the statue is carved, with the style then further specified geographically and historically. Once again, however, the existence of the statue is taken for granted.

In the Japanese context in which our tourist asks, “Why do Chinese gods look like that?” her question points to larger issues. We have noted that the demeanour of Japanese Buddhas is noticeably different from that of Chinese gods. The contrast sharpens when we turn to Shinto shrines, in which there are no god statues at all; Shinto deities remain invisible. If we go a step further in enlarging our context, we encounter Protestant Christianity, Judaism and Islam, religions that taboo any attempt to represent deity in anthroporphic images.

Lin tells us that in Wan-nian, the village in Taiwan where she did her fieldwork, she was told that,

Gods are formless. When you call them, they come! (2008: 459)

They are three feet above your head (Gia-thau sann-chioh u sin-bing; Jutou sanche you shenming)! (2008:460)

They have no shadows and leave no trace (Lai bo-iann, khi bo-cong; Lai wuying, qu wuzong).

Why, then, are there statues of gods on Chinese altars? Lin asks a spirit medium,

Why do people need god statues, and what is the relationship between gods with and without form? (2008:460)

The medium responds,

Everyone respects and prays to gods, but they ‘have no shadows and leave no trace,’ so people carve statues to make the gods settle down where they want them. That means to contain them inside the statues. People should worship the statues, so that a special bond grows between gods and worshippers. If the bond is strong, the spirit won’t leave. (208:460)

As Lin points out, the medium’s interpretation has several implications: people need images in order to believe. Images are places for gods to reside. They also facilitate a particular kind of relationship.

God statues make the formless omnipresent gods settle down and build a stable connection with the villagers, who worship them in return for protection; this creates a strong reciprocal bond between the villagers and the gods. (208:460)

The remainder of Lin’s paper provides a wealth of evidence for this interpretation and focuses, in particular, on steps taken to localize the god’s attachment to a particular community. We may note, however, that while this paper explains in detail how god statues are made, consecrated, and localized, it contains no answer to the question why Chinese god statues depict Chinese gods in the way that they do. We are neither shown or told what these particular statues look like. And one nagging, but fundamental, issue remains. Lin’s informants tell us that Chinese worshippers require images to reinforce their belief and, further, that god statues contribue to creation of strong reciprocal bonds. But why should this be, when worshippers in other traditions do not require images — in fact, their traditions forbid them?

We are still, then, at the point described by Alfred Gell in “The Technology of Enchantment,” when he says of Bourdieu’s sociological approach and Panofsky’s iconographic approach that the former, “ never actually looks at the art object iteself,” while the latter, “treats art as a species of writing” and thus fails to consider the object itself, instead of the symbolic meanings attributed to it (2009: 10). My purpose here is to consider what we might learn by going a step further and considering the object itself.

Adding the Material, Thickening the Description

In this case the object itself is a god statue, the statue of Guandi that sits on the altar of the Guandi Miao in Yokohama’s Chinatown. To learn more about it, I compare it with other representations of Chinese gods, including, in particular, other images of Guandi himself. I want to emphasize, however, that the approach taken here is to add investigation of the material forms in which Guandi is represented to advance a deeper understanding that also includes the other approaches to Chinese religion sketched above. It does not propose to replace them.

The approach I employ is inspired by Claude Levi-Strauss’ injunction in the “Overture” to The Raw and the Cooked to search for the logic in tangible qualities (1970:1) and by Clifford Geertz’ call for thick descriptions in The Interpretation of Cultures (1973). The model I attempt to follow, however, is that provided by Victor Turner in The Ritual Process (1969), enriched by recent discussions of the importance of material cultures and objects to cultural understanding (Miller, 1998; Candlin and Guins, 2009). It is, in other words, informed by Turner’s approach to ethnography but also a contribution to what Daniel Miller calls the second stage in the development of material culture studies, in which the goal is to demonstrate, “what is to be gained by focusing upon the diversity of material worlds which become each other’s contexts rather than reducing them either to models of the social world or to specific subdisciplinary concerns” (1998: 3).

Context is, however, a particularly tricky issue. When Levi-Strauss looks at tangible qualities, he is searching for universal structures that shape cultures everywhere and pointing to binary contrasts, e.g., the raw and the cooked, that appear fundamental in human thinking everywhere. His context is all of humanity. Geertz directs our attention, instead, to the richness of layered meanings that interpreters of culture must seek to unpack in particular situations. He leaves unanswered, however, a fundamental question: where does the relevant context begin or end?

Is it found in that place and moment where the observation is made or the informant’s comment collected? Our tourist is looking at a statue of Guandi in a temple in a Chinatown located in Yokohama, Japan. Is the significance of what she sees confined to this particular temple in this particular location? Or to what someone she meets at the temple may tell her? Or, this being the twenty-first century, should we take as authoritative the account provided on the temple’s Website? If not, how far should we search for connections, in Chinese culture and history? In specific Chinese or religious traditions? Across the length and breadth of Asia? There is, I suggest, no a priori answer. Depending on the observation, any and all of these contexts may be relevant.

When working in a conventional social science framework, the limits of context problem is easy to overlook. We pre-select the scope of our research, develop an hypothesis within it, then search for evidence that confirms or contradicts the hypothesis we are testing. The same is true when doing qualitative research, if we start with a well-defined topic. The topic’s definition defines the limits of relevance.

Invert the problem, however, and start with the observation, the tangible thing itself, a case of something, but we don’t yet know of what. As ethnographers we are not supposed to make assumptions. But, as noted in The SAGE Handbook of Case-based Methods,

From a trans-disciplinary perspective, what unites different kinds of cases, regardless of the discipline, is that all cases are complex and multi-dimensional objects of study. Furthermore, all cases are situated in time and space, as are the disciplines within which they might be situated. Arguably, therefore all cases, as objects of study, need to be described in an ever-increasing and changing variety of ways, and each of these ways may in fact be representing something ‘real’ about the object of study as well. (2009: 141-142)

Thus, for example, when I wrote “Why don’t we see some real money here?” (1990) I began by observing the difference between spirit money and offerings of food in Chinese rituals. I wanted to know why the money was mock money, while the food was real food. Combining ideas from Levi-Strauss and James Fernandez and looking at the ritual process, I developed the hypothesis that the food asserts a relationship; the money restores social distance. In “Negotiating with demons” (1995) I began with the text of a Taoist exorcism and three approaches to analyzing magical language, as performative act, metaphor, and formalized, restricted code. Each did, in fact, show something real about the case in hand, and together the three approaches produced a richer thick description than any one approach by itself.

In this case, I will focus on why some representations of gods are fully rounded figures, seated or standing, some in dynamic poses, while others are literally flat tablets on which a title is written. I will argue, in a Levi-Straussian mode, that this contrast embodies the difference between abstract, and thus absolute, claims to authority and concrete, more personal relationships, rooted in reciprocity that opens the way for exchanges of gifts and favors. I will situate this argument in a Geertzian thick description that builds on existing scholarly analyses of Chinese gods that relate the ways in which gods are envisioned to structure and change in Chinese society. I will speculate on possible extensions of this analysis to comparisons between Chinese popular religion and other religious traditions.

First, however, we need some empirical grounding. Here my model is Victor Turner, who taught us that anthropologists always work with three kinds of data: What we observe, what the people whose lives we study tell us about what we see, and information from other places, ideas and other data that inform interpretation. All are parts of the puzzle from which the anthropologist attempts to construct a convincing picture of the whole of what he is writing about. The place to begin, however, is the way in which the people we study explain their own symbols. I begin, then, with the contents of the Yokohama Guandi Miao website (http://www.yokohama-kanteibyo.com/).

A Twenty-First Century Chinese Temple in Japan

The Yokohama Guandi Miao website (http://www.yokohama-kanteibyo.com/ ) is in Japanese. Its intended audience appears to be Japanese tourists who flock to Yokohama’s Chinatown to enjoy a local but exotic experience. The top page displays a link to Yokohama Chinatown’s own official website (http://www.chinatown.or.jp/). Three additional buttons are indicated on the photograph of the temple’s main gate that is the single largest visual element on the page. Button No. 1 opens a description of the gate, which towers 12 meters above street level. Its elaborate wood carvings are covered with gold leaf, and two dragons sit (one on each side) on the top of its roof. Button No. 2 opens a description of the stone slabs with images of dragons cavorting in the clouds that frame the stairs leading up to the gate. Imported from Beijing, the slabs are single pieces of stone, each weighing four and a half tons. A third, cloud-shaped blue button reads, “Go inside.”

The camera has now moved through the gate, and the temple proper fills the frame. Now there are five buttons that point to information on visually interesting details. Button No. 3 describes the colorful tiles on the roof. Like the stone slabs to which Button No. 2 pointed, these two were specially ordered from Beijing. They are attached with special hooks to enhance rain and wind resistance. Dragons and other beasts made of glass complete the rooftop decorations. Button No. 4 describes four elaborately carved stone columns, two with dragons, two with images of Guandi in action. These were imported from Taiwan. Button No. 5 describes the main incense burner and notes that it is one of five incense burners. Those who wish to worship are directed to purchase five sticks of incense, one for each of the burners. Button No. 6 shows the reception building where incense and spirit money can be purchased. Button No. 7 describes the stone lions that guard the temple, noting that they were imported from Taiwan and survived the fire that in 1986 destroyed the previous version of the temple. Another blue cloud invites the visitor to enter the temple.

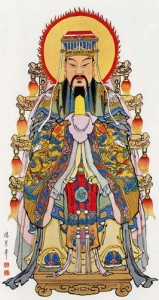

Now the image contains five pictures, each with a button of its own. The largest, which fills three quarters of the frame, shows the main altar, where a seated Guandi, stroking his long beard, looks straight toward the visitor. Button No. 8 reveals the following brief description.

The divine form of Guanyu, a Chinese general who lived around 160 a.d. His loyalty and fidelity have made him a god of commerce worshipped around the world. On his left stands his adopted son, Goan Ping, on his right his faithful follower Zhou Zang. Both also receive worship.

Beneath this description are four phrases highlighted in blue, indicating prayers for which Guandi is especially efficacious: traffic safety, business success, entrance exams, and study.

Buttons No. 9, 10, and 11 point to descriptions of other deities worshipped at the temple: Earth Mother, the Bodhisattva Kwannon, and Tu-di Gong. These also include areas in which these deities are particularly efficacious. Earth Mother, for example, is especially good for those who pray to be safe from disasters and to enjoy good health.

To the left of screen is a menu offering additional information. Here we can discover that this temple is is the fourth in a series, the first of which was built in 1873, shortly after the opening of the port of Yokohama in 1859. The site was enlarged in 1886 and a larger temple built in 1893. That temple was destroyed in the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. The second-generation temple that replaced it was destroyed by Allied bombing in 1945. Its replacement, the third-generation temple, was destroyed by fire in 1986, though miraculously its god statues remained unharmed. Construction of the current temple was completed in 1990. We can also learn that as Chinese began to emigrate overseas in large numbers during the 19th century, temples dedicated to Guandi were built in Chinatowns the world over.

With these facts in mind, we turn now to anthropological and historical discussions of Chinese gods.

Celestial Bureaucracy, The Limits of Metaphor

When our tourist asks, “Why do the gods look like this?” the first answer that comes to mind is that Chinese conceive of their gods as celestial bureaucrats. They wear official robes, and their temples resemble the yamen from which imperial officials governed the Chinese empire. Their ranks correspond to the scale of the territories for which they are responsible. On closer inspection, however, all of these propositions turn out to be dubious.

The idea that Chinese conceive of their gods as celestial bureaucrats was forcefully articulated by Arthur Wolf in the “Introduction” to Religion and Ritual in Chinese Society (1974), a collection of papers that marked a pivotal moment in the anthropological study of Chinese religion and framed subsequent debates. Should Chinese religion be treated as an integrated whole tightly linked to Chinese social structure or a motley bricolage of traditions that, as Donald Deglopper put it (Personal communication; see also 1974: 43-69), stood in relation to Chinese society as the colors refracted by the oil on the surface of a puddle stand to the water in the puddle, a far looser and more liquid relationship?

When this collection appeared, the dominant theories in the anthropology of Chinese society were the structural-functionalism of Maurice Freedman’s studies of lineage organization and the standard marketing regions of G. William Skinner. Synthesized by Stephen Feuchtwang, they provided a plausible grounding for the notion that Chinese spirits fall into three broad categories, gods, ghosts and ancestors. Ancestors were kin whose descendants looked after their worship and afterlife. Ghosts were prototypically hungry ghosts without descendants, angry at their fate. The gods were the spiritual counterparts of government officials, the celestial bureaucrats in charge of dispensing both favors and punishments to those whose lives they ruled. Like their earthly counterparts, they formed a spatial hierarchy, with officials at different levels in charge of smaller or larger geographical areas.

Subsequent research, however, would enormously complicate this picture. Shahar and Weller’s Unruly Gods (1996) provides numerous examples of deities who slip betwixt-and-between Wolf’s categories. Gods, it turned out, frequently started their careers as demons. The Wang-yeh, whose demonic role is to spread plagues, are one example (Katz, 1995). Powerful females like Guan-yin and Mazu had no obvious place in what should have been, in principle, an all-male officialdom. The local gods of the soil, Tu-di Kong, were frequently said to have been virtuous individuals raised to divine status after death; but the territories they governed were at a level far below that to which imperial China’s bureaucracies extended. There is also the awkward fact that the last of the Chinese empires on which the celestial bureaucracy is supposed to be modeled had, by the time that the anthropologists cited here began their research in the 1960s and ‘70s, long since ceased to exist. The Republic of China had been founded in 1911, and the Peoples Republic of China had followed in 1949.

A case might be made for similarity between the powers and habits of modern Chinese bureaucrats and their imperial predecessors. That argument could then be extended to the proposition that Chinese worshipers approach Chinese deities in a way analogous to that in which they approach mortal officials. But as Steve Sangren asks, “If gods are modeled on peasants’ images of officials, why officials so different from any in most peasants’ experience?” (1987: 130). Adam Chau, writing about his observations in Shaanbei, notes that in northern China, too, people liken deities to bureaucrats. He then goes on to note, however, that,

The relationship between local state agents and ordinary peasants in Shaanbei is strained, to put it mildly. Indeed, the image of local bureaucrats in the minds of Shaanbei peasants is most negative: they take things away from you but rarely give anything back (2006:73).

Expectations of bureaucrats and expectations of gods appear to be strikingly different. In Way and Byway (2002), historian Robert Hymes proposes that Chinese deities are conceived in terms of two analytically separate models, one bureaucratic, the other personal. On the one side are officials. Described abstractly, in terms of name, rank, and title, these gods are temporary appointees who represent a multilevel authority imposed from the outside. On the other are individuals with rich biographies; stories about their miracles are legion. Instead of appointed officials, these are extraordinary persons, with inherent powers enhanced through self-cultivation. They enter into direct, dyadic relations with persons and places and are see as permanent fixtures in the localities where they are worshipped. In these respects, they resemble the gods worshipped in Wan-nian, the community studied by Lin Wei-ping, who like the Daoist immortals studied by Hymes, traveled to a particular place where they settled, where their statues are not only consecrated to bring them to life but also localized through rites that attach them to this particular place.

From this perspective, however, the Guandi who sites on the altar in the Guandi Miao in Yokohama’s China is problematic. He is, on the one hand, an intensely individual god. He has a rich biography, elaborated with stories of numerous miracles. He epitomizes abstract virtues, loyalty and righteousness; but is also said to be particularly efficacious in dealing with problems related to traffic safety and achieving business and academic success. His virtues and powers are his own; but the god who occupies his statue may, in fact, be only a delegate, like those said to be worshipped in his place in thousands of temples throughout China and around the world. Neither his virtues nor his stories attach him to one particular place. He is, on the contrary, a favorite deity of overseas Chinese, who have taken him with them as traveled to new places in search of new opportunities. From from being a deity with strong local ties, Guandi is, arguably, the most cosmopolitan of Chinese gods.

Not surprisingly, how Guandi is perceived and the stories told about him vary from place to place and speaker to speaker. How he is seen and represented has been subject for centuries to a process that Prasenjit Duara calls “superscription,” elaboration and editing to suit a variety of purposes (1988:778). In this respect he resembles Lü Dongbin, the Daoist immortal of whom Paul Katz writes that, “more than one Lü Dongin existed in the minds of the late imperial Chinese” (1996: 97). One way of summarizing the argument of this essay would be to say that, like the murals of the Yongle Gong studied by Katz, god statues that represent Guandi are works of art that “have not been adequately used as sources for the study of Chinese hagiography” (1996:72); with the additional caveat that, like the historical documents analyzed by Duara, Chinese god statues are also subject to superscription. They, too, can be elaborated and edited to fit various purposes. These depend, in at least one important respect, to how the relationship between worshipper and god is conceived.

The Importance of Being Ling

One point on which anthropologists of China and their informants appear to agree is that gods are supposed to be ling, i.e., efficacious. How ling should be interpreted is the focus of several attempts to explain the relationship between Chinese deities and the mundane realities of Chinese society.

To Sangren, ling embodies a logic that pervades the whole of Chinese culture and, “can be fully understood only as a product of the reproduction of social institutions and as a manifestation of a native historical consciousness” (1987: 2). Ling refers to situations in which Yang, the principle of order, encompasses and overcomes Yin, the principle of disorder. Deities are ling because they operate at the margin where Yang confronts Yin.

Chau offers a more mundane interpretation that turns on a familiar saying, ren ping shen, shen ping ren (people depend on gods and gods depend on people). A god, he says, is ling, efficacious, when the god responds effectively to his worshippers’ prayers, which leads to the hong huo (red heat) of ritual celebration, which enhances the god’s reputation and makes the god appear more ling (2006:9).

In his review of Miraculous Response, Feuchtwang agrees that Chau is onto something by focusing on the Durkheimian social effervescence that reflects and sustains a god’s reputation for being ling. What is left unaccounted for, he observes, is the “disavowal of human agency” involved in attributing efficacy to the god (2006:978).

Like Sangren, Feuchtwang bases his own analysis on the notion of collective representations that precede and define the attribution of ling to deities. Feuchtwang, however, is not content with a cultural logic that, while pervasive in Chinese rites and religion, is so pervasive that it ceases to account for the different local and historical contexts in which ling appears. He agrees that ling appears at the margins that define the spaces and times in which Chinese individuals find themselves but argues that the frames of reference are multiple — household, community, region, and, only ultimately, China as a whole (Feuchtwang, 2000).

These brief summaries hardly do justice to the complex and subtle arguments of which they are, at best, caricatures. The gods may be Yang overcoming Yin, mark boundaries on several levels of territorial hierarchy, or have won reputations for efficacy reinforced by lavishly decorated temples and noisy celebrations. But, why do they look like that? Why do they display the particular tangible qualities that motivate our tourist’s question? What if, in fact, some representations replace ling, efficaciousness in addressing specific requests, with uncompromising authority? This is an issue to which we will soon return. First, however, we consider iconography, the details by which art historians and collectors identify particular deities and styles of representation.

The Collector’s Eye

Keith Stevens is a collector. According to his Chinese Gods: The Unseen World of Spirits and Demons (1997) he became interested in the iconography of Chinese deities in 1948 and, by the time he wrote this book, had visited more than 3,500 Chinese temples in China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macao, and across Southeast Asia. His personal collection included over 1,000 god statues and 30,000 photographs of temples and images. He had documented the legend and folklore surrounding approximately 2,500 deities.

Stevens candidly describes his book as, “An introduction to the imagery of Chinese deities and demons and their legends and beliefs in relation to the common people, as observed from a Western point of view” (1997:11). His description of Chinese popular religion is consistent with what anthropologists have written. There are, he notes, two orders of deities: a higher order of gods associated with Daoist and Buddhist pantheons and a lower order of humans deified for exceptional accomplishments while alive or miraculous powers after death. The deities on Buddhist altars generally appear in conventional sets; those on Daoist altars or in the temples of popular religion tend to be a more mixed lot. Broadly speaking, he says, there are three standard forms of images.

- In Buddhist images, the faces are calm and characterless, lacking distinctive features. The deities are dressed in simple priestly robes and cross-legged.

- Daoist images may lean, stand or be seated. Characteristic features include black beards, tiny Daoist crowns, and hands holding either a gourd or fly switch.

- The standard deity of popular religion is a seated scholar-official with a full black or red beard, holding a tablet with both hands in front of his chest. Alternatively his hands may rest on arm rests or his knees, or one hand may clutch his official girdle. Alternative elements include the cap, crown or helmet.

These standard forms are only prototypes with numerous variations. Buddhas may be depicted standing, and the deities who serve as their guardians may be demonic in appearance. Daoist images include figures on mythical beasts, like Zhang Dao-ling on his tiger. As previously noted, the deities of popular religion include females and demonic figures whose scowls and gestures are inconsistent with official restraint.

Of particular interest, however, is the way in which Stevens describes his research. Deities can, he notes, be identified in several ways, including titles on placards associated with them or the names of their temples. The groupings in which they appear may also be indicative. Some are easily identified by distinctive iconographic features. But for others there is no recourse but what informants say, and this may be problematic. Here it is, I believe, worth quoting Stevens at length.

A major problem has involved the contradictory stories and legends, with the temple staff giving different versions during successive visits. These contradictions would appear to be due to sheer lack of interest on the part of the temple custodian or to an unwillingness to admit to a foreigner ignorance of the identity of the deities in their temple. Suggestions are usually offered in a confident voice, suggesting unequivocal accuracy. It is only later, on revisiting and perhaps talking to others, that the positive identification becomes less certain. It has been somewhat surprising to me how little many temple watchmen, devotees and even god-carvers know of the myths, legends and histories behind the deities in their own temples and shops (1997:11).

Our second collector, Liu Senhower (劉文三), the author of The God Statues of Taiwan, brings an insider’s perspective to Chinese popular religion. Born in 1939, Liu was a child during World War II. He has vivid memories of his mother, a true believer in popular religion, who made sure that everyone in his family knew how to light incense, bow and worship properly. These memories were reinforced when his father was drafted by the Japanese army and sent to Hainan and his mother prayed day and night for his safety. Then came the Allied bombings and hearing his mother repeating the names of the gods as the family huddled together in their air raid shelter. A story circulated among their neighbors about a bomb that fell into a fishpond instead of the village, diverted by divine intervention. As an artist, author and collector, Liu knows intellectually that god statues are simply blocks of wood, brought to life as works of art by the god-carver’s craft. When he’s tired or troubled, however, they seem to be something more. Liu has a Chinese intellectual’s mixed feelings about the gods, with nuances added by his personal history. He has, however, no trouble identifying the thirty gods whose statues, background and iconography he presents in his book. These are all among the most popular and best documented gods.

With these two collectors to guide us, let us return now to our tourist in Yokohama, looking at the statue on the altar of the Yokohama Guandi Miao (Figure 6).

Describing Guandi

What our tourist sees is an image consistent with the classic description of Guanyu, the hero who would later be deified as Guandi, in The Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

Xuande [Liu Bei] took a look at the man, who stood at a height of nine chi, and had a two chi long beard; his face was the color of a dark jujube, with lips that were red and plump; his eyes were like that of a crimson phoenix, and his eyebrows resembled reclining silkworms. He had a dignified air, and looked quite majestic. (http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Romance_of_the_Three_Kingdoms/Chapter_1#11)

The first of our collectors, Keith Stevens, notes that the legends surrounding Guangong have become the subject for prints, story tellers, operas and plays. He recounts two examples with a more earthy tone than the stories that appear on the Yokohama temple’s website. According to the first, Guanyu was a simple bean curd hawker who rescued a girl from an evil magistrate, whom he killed. He then fled and joined the army. Near Beijing he encountered a butcher who challenged passersby to lift a 400-lb stone off the well in which he stored his meat. Guanyu lifted the stone, took the meat, and was pursued by the butcher, who turned out to be Zhang Fei. The two were fighting when Liu Bei intervened. According to the second, when Guanyu was captured by Cao Cao, he and the wives of Liu Bei were given a single room to share. Guanyu stood by the door all night holding a candle, to avoid any hint of impropriety.

Liu Senhower provides two additional tales. According to one, collected in the countryside in Taiwan, the Jade Emperor, the supreme god in the popular pantheon, had come down to earth to investigate conditions there. Appalled by the human misbehavior he discovered, he was about to punish humanity with devastating disasters and plagues. Hearing of these plans, Guangong prostrated himself before the Jade Emperor and tearfully begged the Jade Emperor to show mercy instead. That is why, the tale says, Guangong’s face is red, from all the crying he did. According to the second, which, I note, also found its way into my field notes, some Chinese believe that Guangong became the Jade Emperor, promoted to the position during the 19th century.

The effect of these tales, considered as superscriptions, is to further humanize Guandi. The awe-inspiring general starts out as a simple beancurd hawker. He may have inhuman self-control; but, like other men, he is subject to sexual temptation. He can cry until he is red in the face. He may, like the founder of a new Chinese dynasty, rise from humble origins to the highest power in the land. But as Robbie Burns once said, “A man’s a man for a’ that.” This god remains approachable.

The opposite is true of another superscription described by Duara.

In 1914 the president of the Republic, Yuan Shikai, ordered the creation of a temple of military heroes devoted to Guandi, Yuefei, and twenty-four lesser heroes. The interior of the main temple in Beijing, with its magnificent timber pillars and richly decorated roof, was impressive in the stately simplicity of its ceremonial arrangements. There were no images. The canonized heroes were representedby their spirit tablets only (1988: 779).

Here there is no mention of ling, no humanizing detail. The message is clear and unequivocal, a pure and uncompromising assertion of the value of loyalty.

Neither wholly abstract and dehumanized nor dynamically ling in appearance, the seated Guang Di on the altar of the Yokohama Guandi Miao falls between these extremes, nicely positioned for a god who is both an epitome of classic virtue and willing to lend a worshipper a hand with a traffic accident, a business problem, or passing a school entrance exam. What happens to the god, however, when his image is globalized?

When Liu analyzes the historical and cultural background to Chinese popular religion in Taiwan, he frequently employs a style of functional analysis that anthropologists associate with Malinowski. The central premise is that Chinese emigrants to Taiwan, struggling to reach and then to carve out new lives on the island found themselves in uncertain and frequently dangerous circumstances. They venerated gods who offered supernatural aid: Mazu, for saving them from the dangers of the four-day sail from the mainland to Taiwan; Tu-di-gong for protecting against storms, drought or other threats to the harvest; Bao-sheng-da-di for protection against and cure of illness.

In this context, Guandi stands out as the epitome of values essential to social order: 仁 (ren, benevolence), 義 (yi, righteousness), 禮 (li, propriety), 智 (zhi, wisdom), and 信 (xin, honesty). His legendary strictness in keeping his promises has made him a favorite deity of businessmen as well as soldiers. His lack of association with any particular set of material dangers may, in addition, make him especially apt as a symbol of morality elevated above the sorts of worldly concerns that motivate worshippers looking for ling. It is thus, I suggest, that since the Qing dynasty, we have found him paired with Confucius, with his wu miao (military temples) built alongside the wen miao (temples of culture) in which Confucius is venerated. It is thus, too, I suggest, that of all the gods in the popular pantheon, he is the one being celebrated globally as a symbol of Chinese culture.

Divine Body Language

At this point we should all be ready to concede of Guandi what Robert Weller (1994) has said about Chinese religion and ritual in general. The forms are familiar. The possible meanings ascribable to them seem endless. They resemble the chemicals suspended in saturated liquids, ready to precipitate in a multitude of forms depending on what is added to them.

Are we left, then, with a generalization of Adam Chau’s conclusion about his Longwanggou case in Shaabei?

No “interpretive community” has emerged out of the cacophonous and “saturated” jumble of texts to present clearly “precipitated” meanings and ideological or theological statements (2006:97).

Let us look once again at the tangible qualities of the statue of Guandi at which our tourist is looking and compare them with other images, first of Guandi and then of other deities.

Google searches for “Guandi, ” “Guangong,” and “Guanyu” yield thousands of images. In most of those clearly identifiable as god statues, we see what we might call “sedate dynamism.” In the seated figures the god seems alert but relaxed. He strokes his beard. His feet are planted on the ground, but his legs are spread but not rigidly squared off. In standing poses the right leg is thrust forward.

The significance of these poses emerges in contrast with other deities. The Jade Emperor is represented sitting four-square, looking straight ahead, his hands joined in front of his chest (Figure 7). In some communities, he is represented only by a tablet bearing his title. He is seen as “too awesome and too powerful to be represented by an image….Among the Fukienese in particular, his spirit was believed to reside in the ash of the main incense pot on the primary altar table in the temple dedicated to him, and not even a tablet is permitted” (Stevens, 1997: 53).

Other spirits who are typically represented by tablets include ancestors and Confucius. In the case of Confucius, we know that until 1530 sculptural images of the Sage were found in state-supported temples all over China and, “the icons’ visual features were greatly influenced by the posthumous titles and ranks that emperor conferred on Confucius and his follows,” treating them, in this respect, like Daoist and Buddhist deities. This treatment aroused the ire of Neo-Confucian ritualists, who led a successful campaign to replace images with tablets and posthumous titles with the designation “Ultimate Sage and First Teacher” (Murray, 2009: 371).

Compared to the Jade Emperor, Guandi seems more relaxed, more human. But compared to other, more dynamic, images, his statues seem sedate. Consider, for example, Xuantianshangdi, possessor of spirit mediums, who is barefoot, with his feet resting on the snake-tortoise who symbolizes the North, the most Yin of all directions (Figure 8). We have noted the legend that describes Guandi as a tofu maker before he became a soldier. A similar legend describes Xuantianshangdi as a butcher and the snake-tortoise as his intestines, torn out in an act of repentance for killing so many living things while plying his butcher’s trade. Guangong is sometimes depicted standing, but his statues are never so dramatically dynamic as those of Nazha, the Third Prince, whose statues depict him standing on his wheels of fire and wielding his spear (Figure 9). In some images, Guangong appears to be frowning, but his face is never so distorted as those of, for example, the goddess Mazu’s demonic attendants Shungfenger, Fair Wind Ears, and Chianliyan, Thousand-Mile Eyes (Figure 10).

With these examples I have, I would argue, briefly sketched an iconographic continuum that stretches from tablets inscribed with text to demonic or once-demonic figures whose dynamic poses or expressions express more humanized, more magical forms of divine power. The statues of Guandi mentioned here represent authority humanized, accessible to human sentiments, but fundamentally righteous. But what of other superscriptions more tailored to the modern world?

Guangong Globalized

Google searches turn up a number of images from manga and video games in which the pre-divine Guanyu, the hero from The Romance of the Three Kingdoms is depicted as a warrior superhero. He glares with intent fury at enemies outside the frame. His robe is slipped off one or both shoulders to reveal a heavily muscled body. In some his pose is similar to that of Nazha on Taiwanese altars. He is shown swooping down thrusting with his halbred. Here, however, I turn to another superscription, Guangong (not, we must note Guandi), as a symbol and salesman for China and Chinese culture.

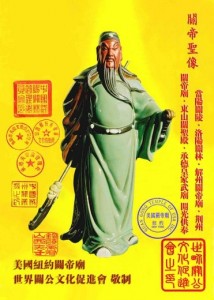

I refer here to another website, World Guangong Culture (世界關公文化, http://www.guangong.hk/). Here, the hero deified as Guandi (Emperor Guan) is presented as Guangong (Honorable Guan). Di, a Chinese character associated with divine or imperial status, has been replaced by gong, which, while formerly the the highest of five orders of nobility and translated “Duke,” is now a common honorific, applied, for example, to a father-in-law.

First up in the list of dignitaries whose statements appear on the site is PRC President Hu Jintao, who says,

In current era, culture has increasingly become the important source of national cohesion and creativity. In addition, it has increasingly become the important factor of the comprehensive national power competition.

He does not mention Guangong by name.

Next is Lui Chun Wan, chairman of the board of directors of the World Guangong Culture Promoting Association, who, after reviewing Guangong’s history, concludes that,

We believe that the rich and colorful Guangong Culture will become a strong force to unite the Chinese people from home and abroad!

There is, however, no mention in his comments of miracles, of magical response, of ling. In this superscription, however, Guangong is not reduced to a title on a tablet, an impersonal abstraction.

The standing image of Guangong chosen to brand the World Guangong Culture Promotion Association shows the god standing and striding confidently forward (Figure 11). In this conspicuously cleaned up version of more traditional depictions of the deity, all traces of armor and glittering gold have been removed. The green of the robe is a paler, more subtle hue than the the blue or green of the more traditional representation. The overall green tone of the image may reflect, I speculate, current “green” concerns with the state of the global environment.

While he does carry his halberd, this version of the god has a warm, modern look, more like a prosperous businessman striding forward to shake your hand than a model of warrior virtues. The “magic” in this image is no longer the traditional ling but instead, I suggest, the economic miracles to be expected from doing business with China.

Beyond China

As we return to where we started, it is, I believe, important to recall that our tourist is looking at the statue of Guandi in a Chinese temple in Yokohama. Our analysis so far has included only Chinese data. Our tourist’s question, however, is motivated by the contrast between what she sees at the Yokohama Guandi Miao and what she has seen elsewhere in Japan, especially when visiting Shinto shrines. There the gods are invisible, posing the question why Chinese temples are filled with god statues, full-figured anthropomorphic representations of gods, while Japanese shrines are not.

Some might question whether an anthropologist should consider such a question at all. Isn’t it wrong, especially when studying religion and ritual, to rip what we see from its cultural context? Isn’t this the kind of speculation for which such 19th century predecessors Sir James Frazer, the author of The Golden Bough, were so roundly condemned by such critics as Sir E. E. Evans-Pirchard who called their work telling “If I were a horse” stories?

But no, this is not what our 19th century predecessors were up to. Frazer and his contemporaries were constructing speculations about the prehistoric origins of religion, a topic for which the direct evidence is very slim, indeed. What I propose here is to extend the method that Robert Weller describes when, having shown that Wolf’s thesis that Chinese gods are bureaucrats is, at best, only party true, then goes on to say,

At a deeper level these cases force us toward some position like Wolf’s: that Chinese religious interpretation moves hand in hand with social experience (1996: 21).

The classic Durkheimian vision in which religion mirrors society may be too simplistic. We now recognize that,

Religion is not a reflex of Chinese social structure, or even of class, gender, or geographical position. It is instead part of an ongoing dialogue of interpretations, sometimes competing and sometimes cooperating (1996:21).

We can, however, go a step further and recognize that the on-going dialogue that Weller describes extends beyond the borders of China. Chinese ideas and images have been absorbed and adapted throughout East Asia and, in some cases—one thinks of Chinese medicine, martial arts, fengsui, the Yin and the Yang—have spread worldwide, carried now by film, video games and the Internet as well as overseas Chinese and other East Asian diasporas. To explore these transmissions and transformations in search of pan-human patterns is far from telling “if I were a horse” stories. It is, instead, the sort of thing that historians do all the time when engaging in comparative research within or across regions or eras, a task that can now be grounded in a rich and growing body of scholarship. In the case of China, we are not dealing with speculation about what happened in prehistory. If anything, we confront the opposite problem; the relevant literature is enormous compared to the number of scholars who research it (McCreery, 2008: 304-305).

In this context, there is, I would argue, much to be said for embracing the “methodological fetishism” that Arjun Appadurai (1986:5, cited in Brown, 2009:142) ascribes to material culture studies. Brown’s “Praesentia” (2009: 177-194) and Michael Taussig’s “In some way or another one can protect oneself from the spirits by portraying them” (2009: 195-207) offer numerous opportunities for close comparison with Lin Wei-Ping’s findings concerning the consecration and localization of god statues in Wan-nian. Closer attention to Chinese god statues reveals not only a richly detailed iconography but also general principles that have broader implications. They make inescapable the larger question: Why are Chinese gods, like the gods of Hindu India and ancient Greece and Rome, Christian saints and Christ himself represented in human form?

The kami venerated in Japanese shrines are concealed from their worshippers. Only priests may see the sacred regalia in which they reside when invited to participate in Shinto ceremonies (Nelson, 1997). We have seen that when held in greatest awe, the Jade Emperor is also invisible: a feature he also shares with the gods of the Old Testament, Calvin and the Holy Koran.

What we see here in tablets, books and other non-anthropomorphic forms of material representation is, I would argue, a precise analogue to Maurice Bloch’s description of ritual language as a language deliberately impoverished to force particular interpretations (cited in McCreery, 1995: 158). Abstraction and formalization assert unimpeachable authority. Conversely, however, concrete representations, and especially those that take a full-figured anthropomorphic form, render the gods approachable, transforming them into patrons with whom it is possible to form particularistic relationships in which both emotion and exchange can be used to secure the gods’ favor.

In this paper we have seen anthropologists whose eyes are focused beyond what they see, on theories that purport to explain how Chinese culture or society works. We have seen collectors, whose iconographic perspectives draw our attention back to the visual evidence that our eyes provide and noted the diversity of stories that add meaning to what we see. The author has sketched one dimension of a visual grammar, a continuum that extends from authority abstracted in inscribed tablets to power expressed in near-demonic forms.

There are no final answers here. If, however, we open our eyes to the tangible qualities we find in Chinese god statues, we will, I suggest, be able to write thicker descriptions, descriptions that challenge our theories and demand more subtle ones, theories that may, at the end of the day, enable us to situate Chinese religion more firmly in relation to religion as a human phenomenon.

References

Appadurai, Arjun (1986), “Introduction: Commodities and the Politics of Value,” in Arjun Appadurai, ed., The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge U. Press.

Brown, Peter (2009) “Thing Theory, ” in Fiona Candlin and Raiford Guins, eds., The Object Reader. London: Routledge, pp. 139-152.

Brown, Peter (2009) “Prasentia, ” in Fiona Candlin and Raiford Guins, eds., The Object Reader. London: Routledge, pp. 177-194.

Byrne, David and Charles C. Ragin, eds. (2009), The SAGE Handbook of Case-Based Methods. Sage Publications, Ltd.

Chau, Adam Yuet (2006) Miraculous Response: Doing Popular Religion in Contemporary China. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

DeGlopper, Donald (1974) “Religion and Ritual in Lukang,” In Arthur Wolf, ed., Religion and Ritual in Chinese Society. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Feuchtwang, Stephan (2001) Popular Religion in China: The Imperial Metaphor. Richmond, England: Curzon Press.

Feuchtwang, Stephan (2006) “Miraculous Response: Doing Popular Religion in Contemporary China.” In Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 12:4:978.

Geertz, Clifford (1973) The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books, Inc.

Gell, Alfred (2009) “The Technology of Enchantment and the Enchantment of Technology, ” in Fiona Candlin and Raiford Guins, eds., The Object Reader. London: Routledge, pp. 208-228.

Katz, Paul R. (1995) Demon Hordes and Burning Boats: The Cult of Marshal Wen in Late Imperial Chekiang (Suny Series in Chinese Local Studies) New York: State University of New York Press.

Katz, Paul R. (1996) “Enlightened Alchemist or Immoral Immortal? The Growth of Lü Dongbin’s Cult in Late Imperial China,” in Shahar and Weller, eds., Unruly Gods: Divinity and Society in China. Honolulu: U. of Hawaii Press, pp. 70-104.

Lin Wei-Ping (2008) “Conceptualizing Gods through Statues: A Study of Personification and Localization in Taiwan,” Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 50, No. 2: pp. 454-477.

Liu Senhower (劉文三) (1981) The God Statues of Taiwan (台灣神像藝術). Taipei: Yishuchia Press.

McCreery, John (1990) “Why Don’t We See Some Real Money Here? Offerings in Chinese Religion. Journal of Chinese Religion 18:1-24.

McCreery, John (1995) “Negotiating with Demons: The Uses of Magical Language. American Ethnologist 22:1:144-164.

McCreery, John (2008), “Traditional Religions of China” in Ray Scupin, ed., Religion and Culture, An Anthropological Focus, 2nd edition. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice-Hall.

Miller, Daniel, ed. (1998) Material cultures: Why some things matter. Chicago: Chicago University Press

Murray, Julia K. (2009) “‘Idols’ in the Temple: Icons and the Cult of Confucius.” The Journal of Asian Studies 68:2:371-411.

Nelson, John K. (1997) A Year in the Life of a Shinto Shrine. University of Washington Press.

Sangren, Steven (1987) History and Magical Power in a Chinese Community. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Shahar, Meir and Ropert P. Weller, eds. (1996), Unruly Gods: Divinity and Society in China. Honolulu: U. of Hawaii Press.

Stevens, Keith (1997) Chinese Gods: The Unseen World of Spirits and Demons. London: Collins & Brown Ltd.

Taussig, Michael (2009) “In some way or another one can protect oneself from the spirits by portraying them, ” in Fiona Candlin and Raiford Guins, eds., The Object Reader. London: Routledge, pp. 195-207.

Weller, Robert P. (1994) Resistance, Chaos, and Control in China: Taiping Rebels, Taiwanese Ghosts, and Tiananmen. University of Washington Press.

Wolf, Arthur, ed. (1974) Religion and Ritual in Chinese Society. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Figures

Figure 1: The Yokohama Guandi Miao (Exterior)

Figure 2: Sengen Jinja (a Shinto Shrine)

Figure 3: Guandi on the altar of the Yokohama Guandi Miao

Figure 4: Japanese Buddha

Figure 5: Shinkoyasu Jinja (Interior)

Figure 6: Guandi at the Yokohama Guandi Miao

Figure 7: The Jade Emperor

Figure 8: Xuantianshangdi

Figure 9: Nahza, The Third Prince

Figure 10: Thousand-Mile Eyes

Figure 11: Guangong on the Guangong World Culture website

Prologue

I invite you to imagine a tourist visiting Japan. She has seen a number of Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines. Friends take her to Yokohama’s Chinatown for dinner. On the way to the restaurant they stop for a look at a Chinese temple, the Guandi Miao. The vivid colors and baroque decoration of the Chinese temple contrasts sharply with the subdued simplicity of Japanese Buddhist temples and shrines (Figures 1, and 2). The red face and piercing eyes of the Chinese deity on this altar (Figure 3 differ dramatically from the lowered eye-lids and meditative serenity of the Japanese Buddhas (Figure 4) she has seen. In Japanese Shinto shrines, the gods are not visible at all (Figure 5). The question she asks is simple but profound: “Why do Chinese gods look like that?”

When, however, we turn to the anthropological literature on Chinese religion, we discover, as Wei-Ping Lin points out, that anthropologists have paid little attention to the material forms that gods take in their statues on Chinese altars (2008:454-455). Instead of looking closely at god statues to discover what they might tell us about the gods in question, we have tended to look through god statues in search of something else. The statues themselves are treated as arbitrary signs, as, in effect, texts, whose material form is of no intrinsic interest.

If we adopt, instead, an art historical or connoisseur’s perspective, we encounter a different approach. Here the primary focus of interest is iconographic details that that identify the god or the style in which the statue is carved, with the style then further specified geographically and historically. Once again, however, the existence of the statue is taken for granted.

In the Japanese context in which our tourist asks, “Why do Chinese gods look like that?” her question points to larger issues. We have noted that the demeanour of Japanese Buddhas is noticeably different from that of Chinese gods. The contrast sharpens when we turn to Shinto shrines, in which there are no god statues at all; Shinto deities remain invisible. If we go a step further in enlarging our context, we encounter Protestant Christianity, Judaism and Islam, religions that taboo any attempt to represent deity in anthroporphic images.

Lin tells us that in Wan-nian, the village in Taiwan where she did her fieldwork, she was told that,

Gods are formless. When you call them, they come! (2008: 459)

They have no shadows and leave no trace (Lai bo-iann, khi bo-cong; Lai wuying, qu wuzong).

They are three feet above your head (Gia-thau sann-chioh u sin-bing; Jutou sanche you shenming)! (2008:460)

Why, then, are there statues of gods on Chinese altars? Lin asks a spirit medium,

Why do people need god statues, and what is the relationship between gods with and without form? (2008:460)

The medium responds,

Everyone respects and prays to gods, but they ‘have no shadows and leave no trace,’ so people carve statues to make the gods settle down where they want them. That means to contain them inside the statues. People should worship the statues, so that a special bond grows between gods and worshippers. If the bond is strong, the spirit won’t leave. (208:460)

As Lin points out, the medium’s interpretation has several implications: people need images in order to believe. Images are places for gods to reside. They also facilitate a particular kind of relationship.

God statues make the formless omnipresent gods settle down and build a stable connection with the villagers, who worship them in return for protection; this creates a strong reciprocal bond between the villagers and the gods. (208:460)

The remainder of Lin’s paper provides a wealth of evidence for this interpretation and focuses, in particular, on steps taken to localize the god’s attachment to a particular community. We may note, however, that while this paper explains in detail how god statues are made, consecrated, and localized, it contains no answer to the question why Chinese god statues depict Chinese gods in the way that they do. We are neither shown or told what these particular statues look like. And one nagging, but fundamental, issue remains. Lin’s informants tell us that Chinese worshippers require images to reinforce their belief and, further, that god statues contribue to creation of strong reciprocal bonds. But why should this be, when worshippers in other traditions do not require images — in fact, their traditions forbid them?

We are still, then, at the point described by Alfred Gell in “The Technology of Enchantment,” when he says of Bourdieu’s sociological approach and Panofsky’s iconographic approach that the former, “ never actually looks at the art object iteself,” while the latter, “treats art as a species of writing” and thus fails to consider the object itself, instead of the symbolic meanings attributed to it (2009: 10). My purpose here is to consider what we might learn by going a step further and considering the object itself.

Adding the Material, Thickening the Description

In this case the object itself is a god statue, the statue of Guandi that sits on the altar of the Guandi Miao in Yokohama’s Chinatown. To learn more about it, I compare it with other representations of Chinese gods, including, in particular, other images of Guandi himself. I want to emphasize, however, that the approach taken here is to add investigation of the material forms in which Guandi is represented to advance a deeper understanding that also includes the other approaches to Chinese religion sketched above. It does not propose to replace them.

The approach I employ is inspired by Claude Levi-Strauss’ injunction in the “Overture” to The Raw and the Cooked to search for the logic in tangible qualities (1970:1) and by Clifford Geertz’ call for thick descriptions in The Interpretation of Cultures (1973). The model I attempt to follow, however, is that provided by Victor Turner in The Ritual Process (1969), enriched by recent discussions of the importance of material cultures and objects to cultural understanding (Miller, 1998; Candlin and Guins, 2009). It is, in other words, informed by Turner’s approach to ethnography but also a contribution to what Daniel Miller calls the second stage in the development of material culture studies, in which the goal is to demonstrate, “what is to be gained by focusing upon the diversity of material worlds which become each other’s contexts rather than reducing them either to models of the social world or to specific subdisciplinary concerns” (1998: 3).

Context is, however, a particularly tricky issue. When Levi-Strauss looks at tangible qualities, he is searching for universal structures that shape cultures everywhere and pointing to binary contrasts, e.g., the raw and the cooked, that appear fundamental in human thinking everywhere. His context is all of humanity. Geertz directs our attention, instead, to the richness of layered meanings that interpreters of culture must seek to unpack in particular situations. He leaves unanswered, however, a fundamental question: where does the relevant context begin or end?

Is it found in that place and moment where the observation is made or the informant’s comment collected? Our tourist is looking at a statue of Guandi in a temple in a Chinatown located in Yokohama, Japan. Is the significance of what she sees confined to this particular temple in this particular location? Or to what someone she meets at the temple may tell her? Or, this being the twenty-first century, should we take as authoritative the account provided on the temple’s Website? If not, how far should we search for connections, in Chinese culture and history? In specific Chinese or religious traditions? Across the length and breadth of Asia? There is, I suggest, no a priori answer. Depending on the observation, any and all of these contexts may be relevant.

When working in a conventional social science framework, the limits of context problem is easy to overlook. We pre-select the scope of our research, develop an hypothesis within it, then search for evidence that confirms or contradicts the hypothesis we are testing. The same is true when doing qualitative research, if we start with a well-defined topic. The topic’s definition defines the limits of relevance.

Invert the problem, however, and start with the observation, the tangible thing itself, a case of something, but we don’t yet know of what. As ethnographers we are not supposed to make assumptions. But, as noted in The SAGE Handbook of Case-based Methods,

-

-

From a trans-disciplinary perspective, what unites different kinds of cases, regardless of the discipline, is that all cases are complex and multi-dimensional objects of study. Furthermore, all cases are situated in time and space, as are the disciplines within which they might be situated. Arguably, therefore all cases, as objects of study, need to be described in an ever-increasing and changing variety of ways, and each of these ways may in fact be representing something ‘real’ about the object of study as well (2009: 141-142)

-

Thus, for example, when I wrote “Why don’t we see some real money here?” (1990) I began by observing the difference between spirit money and offerings of food in Chinese rituals. I wanted to know why the money was mock money, while the food was real food. Combining ideas from Levi-Strauss and James Fernandez and looking at the ritual process, I developed the hypothesis that the food asserts a relationship; the money restores social distance. In “Negotiating with demons” (1995) I began with the text of a Taoist exorcism and three approaches to analyzing magical language, as performative act, metaphor, and formalized, restricted code. Each did, in fact, show something real about the case in hand, and together the three approaches produced a richer thick description than any one approach by itself.

In this case, I will focus on why some representations of gods are fully rounded figures, seated or standing, some in dynamic poses, while others are literally flat tablets on which a title is written. I will argue, in a Levi-Straussian mode, that this contrast embodies the difference between abstract, and thus absolute, claims to authority and concrete, more personal relationships, rooted in reciprocity that opens the way for exchanges of gifts and favors. I will situate this argument in a Geertzian thick description that builds on existing scholarly analyses of Chinese gods that relate the ways in which gods are envisioned to structure and change in Chinese society. I will speculate on possible extensions of this analysis to comparisons between Chinese popular religion and other religious traditions.

First, however, we need some empirical grounding. Here my model is Victor Turner, who taught us that anthropologists always work with three kinds of data: What we observe, what the people whose lives we study tell us about what we see, and information from other places, ideas and other data that inform interpretation. All are parts of the puzzle from which the anthropologist attempts to construct a convincing picture of the whole of what he is writing about. The place to begin, however, is the way in which the people we study explain their own symbols. I begin, then, with the contents of the Yokohama Guandi Miao website (http://www.yokohama-kanteibyo.com/).

A Twenty-First Century Chinese Temple in Japan

The Yokohama Guandi Miao website (http://www.yokohama-kanteibyo.com/ ) is in Japanese. Its intended audience appears to be Japanese tourists who flock to Yokohama’s Chinatown to enjoy a local but exotic experience. The top page displays a link to Yokohama Chinatown’s own official website (http://www.chinatown.or.jp/). Three additional buttons are indicated on the photograph of the temple’s main gate that is the single largest visual element on the page. Button No. 1 opens a description of the gate, which towers 12 meters above street level. Its elaborate wood carvings are covered with gold leaf, and two dragons sit (one on each side) on the top of its roof. Button No. 2 opens a description of the stone slabs with images of dragons cavorting in the clouds that frame the stairs leading up to the gate. Imported from Beijing, the slabs are single pieces of stone, each weighing four and a half tons. A third, cloud-shaped blue button reads, “Go inside.”

The camera has now moved through the gate, and the temple proper fills the frame. Now there are five buttons that point to information on visually interesting details. Button No. 3 describes the colorful tiles on the roof. Like the stone slabs to which Button No. 2 pointed, these two were specially ordered from Beijing. They are attached with special hooks to enhance rain and wind resistance. Dragons and other beasts made of glass complete the rooftop decorations. Button No. 4 describes four elaborately carved stone columns, two with dragons, two with images of Guandi in action. These were imported from Taiwan. Button No. 5 describes the main incense burner and notes that it is one of five incense burners. Those who wish to worship are directed to purchase five sticks of incense, one for each of the burners. Button No. 6 shows the reception building where incense and spirit money can be purchased. Button No. 7 describes the stone lions that guard the temple, noting that they were imported from Taiwan and survived the fire that in 1986 destroyed the previous version of the temple. Another blue cloud invites the visitor to enter the temple.

Now the image contains five pictures, each with a button of its own. The largest, which fills three quarters of the frame, shows the main altar, where a seated Guandi, stroking his long beard, looks straight toward the visitor. Button No. 8 reveals the following brief description.

The divine form of Guanyu, a Chinese general who lived around 160 a.d. His loyalty and fidelity have made him a god of commerce worshipped around the world. On his left stands his adopted son, Goan Ping, on his right his faithful follower Zhou Zang. Both also receive worship.

Beneath this description are four phrases highlighted in blue, indicating prayers for which Guandi is especially efficacious: traffic safety, business success, entrance exams, and study.

Buttons No. 9, 10, and 11 point to descriptions of other deities worshipped at the temple: Earth Mother, the Bodhisattva Kwannon, and Tu-di Gong. These also include areas in which these deities are particularly efficacious. Earth Mother, for example, is especially good for those who pray to be safe from disasters and to enjoy good health.

To the left of screen is a menu offering additional information. Here we can discover that this temple is is the fourth in a series, the first of which was built in 1873, shortly after the opening of the port of Yokohama in 1859. The site was enlarged in 1886 and a larger temple built in 1893. That temple was destroyed in the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. The second-generation temple that replaced it was destroyed by Allied bombing in 1945. Its replacement, the third-generation temple, was destroyed by fire in 1986, though miraculously its god statues remained unharmed. Construction of the current temple was completed in 1990. We can also learn that as Chinese began to emigrate overseas in large numbers during the 19th century, temples dedicated to Guandi were built in Chinatowns the world over.

With these facts in mind, we turn now to anthropological and historical discussions of Chinese gods.

Celestial Bureaucracy, The Limits of Metaphor

When our tourist asks, “Why do the gods look like this?” the first answer that comes to mind is that Chinese conceive of their gods as celestial bureaucrats. They wear official robes, and their temples resemble the yamen from which imperial officials governed the Chinese empire. Their ranks correspond to the scale of the territories for which they are responsible. On closer inspection, however, all of these propositions turn out to be dubious.

The idea that Chinese conceive of their gods as celestial bureaucrats was forcefully articulated by Arthur Wolf in the “Introduction” to Religion and Ritual in Chinese Society (1974), a collection of papers that marked a pivotal moment in the anthropological study of Chinese religion and framed subsequent debates. Should Chinese religion be treated as an integrated whole tightly linked to Chinese social structure or a motley bricolage of traditions that, as Donald Deglopper put it (Personal communication; see also 1974: 43-69), stood in relation to Chinese society as the colors refracted by the oil on the surface of a puddle stand to the water in the puddle, a far looser and more liquid relationship?

When this collection appeared, the dominant theories in the anthropology of Chinese society were the structural-functionalism of Maurice Freedman’s studies of lineage organization and the standard marketing regions of G. William Skinner. Synthesized by Stephen Feuchtwang, they provided a plausible grounding for the notion that Chinese spirits fall into three broad categories, gods, ghosts and ancestors. Ancestors were kin whose descendants looked after their worship and afterlife. Ghosts were prototypically hungry ghosts without descendants, angry at their fate. The gods were the spiritual counterparts of government officials, the celestial bureaucrats in charge of dispensing both favors and punishments to those whose lives they ruled. Like their earthly counterparts, they formed a spatial hierarchy, with officials at different levels in charge of smaller or larger geographical areas.

Subsequent research, however, would enormously complicate this picture. Shahar and Weller’s Unruly Gods (1996) provides numerous examples of deities who slip betwixt-and-between Wolf’s categories. Gods, it turned out, frequently started their careers as demons. The Wang-yeh, whose demonic role is to spread plagues, are one example (Katz, 1995). Powerful females like Guan-yin and Mazu had no obvious place in what should have been, in principle, an all-male officialdom. The local gods of the soil, Tu-di Kong, were frequently said to have been virtuous individuals raised to divine status after death; but the territories they governed were at a level far below that to which imperial China’s bureaucracies extended. There is also the awkward fact that the last of the Chinese empires on which the celestial bureaucracy is supposed to be modeled had, by the time that the anthropologists cited here began their research in the 1960s and ‘70s, long since ceased to exist. The Republic of China had been founded in 1911, and the Peoples Republic of China had followed in 1949.

A case might be made for similarity between the powers and habits of modern Chinese bureaucrats and their imperial predecessors. That argument could then be extended to the proposition that Chinese worshipers approach Chinese deities in a way analogous to that in which they approach mortal officials. But as Steve Sangren asks, “If gods are modeled on peasants’ images of officials, why officials so different from any in most peasants’ experience?” (1987: 130). Adam Chau, writing about his observations in Shaanbei, notes that in northern China, too, people liken deities to bureaucrats. He then goes on to note, however, that,

-

-

The relationship between local state agents and ordinary peasants in Shaanbei is strained, to put it mildly. Indeed, the image of local bureaucrats in the minds of Shaanbei peasants is most negative: they take things away from you but rarely give anything back (2006:73).

-

-

Expectations of bureaucrats and expectations of gods appear to be strikingly different.

In Way and Byway (2002), historian Robert Hymes proposes that Chinese deities are conceived in terms of two analytically separate models, one bureaucratic, the other personal. On the one side are officials. Described abstractly, in terms of name, rank, and title, these gods are temporary appointees who represent a multilevel authority imposed from the outside. On the other are individuals with rich biographies; stories about their miracles are legion. Instead of appointed officials, these are extraordinary persons, with inherent powers enhanced through self-cultivation. They enter into direct, dyadic relations with persons and places and are see as permanent fixtures in the localities where they are worshipped. In these respects, they resemble the gods worshipped in Wan-nian, the community studied by Lin Wei-ping, who like the Daoist immortals studied by Hymes, traveled to a particular place where they settled, where their statues are not only consecrated to bring them to life but also localized through rites that attach them to this particular place.

From this perspective, however, the Guandi who sites on the altar in the Guandi Miao in Yokohama’s China is problematic. He is, on the one hand, an intensely individual god. He has a rich biography, elaborated with stories of numerous miracles. He epitomizes abstract virtues, loyalty and righteousness; but is also said to be particularly efficacious in dealing with problems related to traffic safety and achieving business and academic success. His virtues and powers are his own; but the god who occupies his statue may, in fact, be only a delegate, like those said to be worshipped in his place in thousands of temples throughout China and around the world. Neither his virtues nor his stories attach him to one particular place. He is, on the contrary, a favorite deity of overseas Chinese, who have taken him with them as traveled to new places in search of new opportunities. From from being a deity with strong local ties, Guandi is, arguably, the most cosmopolitan of Chinese gods.

Not surprisingly, how Guandi is perceived and the stories told about him vary from place to place and speaker to speaker. How he is seen and represented has been subject for centuries to a process that Prasenjit Duara calls “superscription,” elaboration and editing to suit a variety of purposes (1988:778). In this respect he resembles Lü Dongbin, the Daoist immortal of whom Paul Katz writes that, “more than one Lü Dongin existed in the minds of the late imperial Chinese” (1996: 97). One way of summarizing the argument of this essay would be to say that, like the murals of the Yongle Gong studied by Katz, god statues that represent Guandi are works of art that “have not been adequately used as sources for the study of Chinese hagiography” (1996:72); with the additional caveat that, like the historical documents analyzed by Duara, Chinese god statues are also subject to superscription. They, too, can be elaborated and edited to fit various purposes. These depend, in at least one important respect, to how the relationship between worshipper and god is conceived.

The Importance of Being Ling

One point on which anthropologists of China and their informants appear to agree is that gods are supposed to be ling, i.e., efficacious. How ling should be interpreted is the focus of several attempts to explain the relationship between Chinese deities and the mundane realities of Chinese society.

To Sangren, ling embodies a logic that pervades the whole of Chinese culture and, “can be fully understood only as a product of the reproduction of social institutions and as a manifestation of a native historical consciousness” (1987: 2). Ling refers to situations in which Yang, the principle of order, encompasses and overcomes Yin, the principle of disorder. Deities are ling because they operate at the margin where Yang confronts Yin.

Chau offers a more mundane interpretation that turns on a familiar saying, ren ping shen, shen ping ren (people depend on gods and gods depend on people). A god, he says, is ling, efficacious, when the god responds effectively to his worshippers’ prayers, which leads to the hong huo (red heat) of ritual celebration, which enhances the god’s reputation and makes the god appear more ling (2006:9.

In his review of Miraculous Response, Feuchtwang agrees that Chau is onto something by focusing on the Durkheimian social effervescence that reflects and sustains a god’s reputation for being ling. What is left unaccounted for, he observes, is the “disavowal of human agency” involved in attributing efficacy to the god (2006:978).

Like Sangren, Feuchtwang bases his own analysis on the notion of collective representations that precede and define the attribution of ling to deities. Feuchtwang, however, is not content with a cultural logic that, while pervasive in Chinese rites and religion, is so pervasive that it ceases to account for the different local and historical contexts in which ling appears. He agrees that ling appears at the margins that define the spaces and times in which Chinese individuals find themselves but argues that the frames of reference are multiple — household, community, region, and, only ultimately, China as a whole (Feuchtwang, 2000).